|

Disclaimer: This unedited, rough draft material is a year-long project in response to our 2004 theme: pilgrimage. It is meant to be a dialogue between myself and my fellow Mammoths and any of you who happen along. It is intentionally not polished, nor is it finished. Charlie Buchman Ellis -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- An odd experience this afternoon in the Jungian Seminar. My analyst, John Desteian, taught this class and for the last two sessions we have done independent dream analysis, as I discussed a week or so ago. Early in the process he asked us to turn in dreams for classmates to analyze, so I turned one in quite a while ago, four months maybe. Today, mine came up. Here it is:

Winter Solstice Night, 2003

I had the task of clearing debris from a fast-flowing stream. I moved trees, cleared brush gathered under overhanging limbs, and worked my way upstream. As I moved, I realized I had begun to work my way up a steep mountain toward the Streamís source. The closer I got to the peak, the fewer obstructions I found, so I focused on climbing up to the source. Near the top I found a road pitched at an extreme angle, and I began to hike up the shoulder of the road. As I got near the top, the angle became so sever that I pitched over, landed on my butt, and began to slide slowly, then faster toward a network of highways at the base of the mountain. I knew one exit would lead to side streets where I could decelerate easily, but I missed the turn and sped down toward a four-lane divided highway. I feared cars and trucks since I was close the pavement and hard to see. With some luck I maneuvered on the four-lanes and ended up in town. Safe.

As my classmate Pat began her analysis, sweat popped out on my palms. Pat, a Ph.D. in genetics and chemistry, now studying for her Psychology Ph.D. plows a pretty straight path. Analysis, not imagination, is her long suit. I mention this because it was a peculiar situation: a classmate, unbeknownst to her, had my dream, on which she proceeded to work. John had forgotten it was my dream (I put my name on it when I e-mailed it to him.) and was offering his insights, too. I chose not to reveal myself as the dreamer at first out of curiousity, then, as the analysis went forward, I felt less and less like opening upóa strange combination of shame (about exposure, not any specific dream content or conclusions), respect for my colleagues who were doing their best (everyone thought the dreamer was a woman.), and, finally, I felt Iíd waited too long, so I kept quiet. In the end the analysis was helpful to me, and seemed to describe an actual psychological moment for me, to wit: John said the dream could be an example of an opus contra natarum, a work against nature. Hereís a brief description: ďOnce upon a time there were scientists who did just that: the alchemists. They deliberately undertook the opus contra naturam the great work of uniting opposites and transforming the given basic material into the highest value. They knew of the dangers of this undertaking; the knowledge that their work could be successful only, Deo volente, was their protection against inflation and against being overwhelmed by their images; they knew also that intellectual knowledge by itself has little value: transformation implies insight, a re-cognition, seeing, realizing on all levels and centres, which then perhaps is nearer to the idea of wisdom than of knowledge.Ē And another... ďThe work or opus of alchemy was an inner repetition of the cosmology outside - except, on the psychological level, the alchemical process was a complete reversal of our contemporary notion of biological evolution - as an expanding, outer process on the physical plane. Its final 'goal' was inorganic matter, either a metal (notably, gold), a mineral, a crystal or a stone. This is dissimilar to the seven-day creation story in Genesis, for instance, where man is the crown of creation, the top of the evolutionary ladder. In other words, alchemy's operations deliberately broke down the natural order of things in order to renew creation. It was a work against nature, an opus contra naturam, in order to free the psyche from its material and natural view of itself and the world. This return to find original essence, the gold in the heart of matter, may be explained by man's relation to the material world of nature. Mircea Eliade5 traces the relationship of alchemy and metallurgy of primitive man to mineral substances. ď The opus contra naturam is in the service of individuation. The slide down the mountain is a regression to a place of safety from which the opus can begin again to attack the mountain. I felt exposed and vulnerable during this process, but, in the end, found it useful because I got a lot of insight into this dream, and how to approach dreams from the exercise of both analyzing a dream myself (last month) and having a dream of mine analyzed in the group. I also had the added benefit of having my analyst add his insight to the mix. All in all, a helpful process. It did make me wonder, as Tom suggested a year or so ago, whether a special dream work time for the Woollyís might prove useful to us. I know there are people out there who facilitate dream groups. It feels like it might be worth exploring. Especially as an aid to the notion of pilgrimage as interior journeyóand one with its nighttime paths as well as its daylight ones. It also moved me into the general idea of sacred mountains, like Bear Butte, Devilís Tower, Ship Rock, Mt. Meru, Mt. Kaillas, Olympus, Mt. Sinai, Mt. Tabor, Mt. Ararat and the mountain as place for pilgrimage.

Iím intrigued by the notion of life as an opus contra nataram, since one way to look at life is as an animation of matter, an animation subject in the end to the ruthless laws of entropy, yet while in motion, a wonder to behold. Looking back I can see this as the source of the amazement I experienced when I saw into the wolfís chest. Tonight, at the opening of the Twinís season, Iím reminded of a book, Time Begins on Opening Day. I donít recall the conceit, but the notion fits with life as an opus contra nataram. Each season, each team begins a journey through a series of chaotic events i.e., games, health of individual players, relative talent between and among players, weather, expanding and contracting strike zones. A coachís job is to evoke order out of all this and produce a winning season. As the Cubs have consistently shown, this is an opus contra nataram. Even, it occurs to me, too, the arc of a pitched ball or a ball springing off the bat or one thrown from Tinkerís to Everís to Chance is also such a work. In each case work applied to the ball attempts to overcome gravity. The inevitable failure of this work is, in fact, often part of the play, and a key part at that. Perhaps this is all somehow a metaphor for individuation, but I donít see how. Yesterday morning (Sunday) I had the good fortune to give a presentation (attached) about the notion of sacred journey with Kate, Tom, and Paul present. It was fun to have the worlds of the Woollyís and the UUís and home meet. The UUís were, predictably, squeamish about the notion of the sacred (hoping against hope that I wasnít talking about...well, you know.god.)

I think theyíre more worried about this one, to be honest:

And with good reason. Talk about an opus contra nataram. Iím amazed at how vulnerable I am on the days I give presentations. Kate reminded me of how tongue tied I got at the very start and I thought Ė ohmigod. Sheís right. I was terrible. I must be stupid. Why donít I have this down yet? Theyíll never want me back. This just goes to prove...all manner of unrelated negative things Iíve suspect all along. So, I went to sleep with bad juju floating all around me. Got up the next morning and it had lifted. Iíve learned in the Jungian seminar about things called complexes, accretions of feelings and ideas and memories clustered around a constellating or precipitating core. Iíd heard the word before, but somehow it never developed a concrete reality for me until now. In the morning I realized I had wandered into a complex, probably one constellated around my imaginal image of my fatherís image of me: a bumbler with, ultimately, no real skills, and bound to fail. Not a guy who could get involved in anything serious and succeed because eventually heíd be found out, exposed. Over time I managed to energize this complex whenever I experienced a perceived slip: angry words to someone or from someone, a B for godís sake, losing the power of speech during a sermon, any, in other words, of the uncounted and uncountable, normal dips in a life. Pilgrimage accounts for this phenomena and gives us a tool for life. On the road it is common to despair, to lose hope, to believe the obstacles too hard, the troubles out of control. And the way to meet them is to ask whether the troubles or the journey has more power, more significance, more value. In the backwaters of Oaxaca the taxi-driver who has decided a demon chases his vehicle and he, personally, can escape if only he drives fast enough, is an obstacle. A tip for slowing down can bring him back to the awareness that completion of the trip assures the demon will lose; you will live to fight it in good health. 95% of Americans fear public speaking more than death. Strange, as they say, but true. Iíve been a public speaker almost all my life and have only very occasionally succumbed to this fear. It happens for me when something tiny goes wrong. Sunday AM I read some words in an eytmology Iíd cut and pasted. And the words made no sense. So, I tried to think, while talking, how I should adjust. Turns out I couldnít do both at the same time. So what? I couldnít. Sure enough, this morning I had an e-mail asking me for a copy of the sermon and for dates of availability in the next church year. So, there. Complex. Complexes are, in fact, the demons which pursue us; and, their reality and power is not analgous to demons, but the same. When they come and attack us, their power to destroy us is strong, depending on the complex, and it can be complete. Our pilgrim journey is, in part, to expose our demons along the way, learn their ways, and, if we can, exorcise them; if we canít, then learn how to dampen and dimish their corrosive power. St. Anthony was a great demon fighter and I close this piece with an image of him at work:

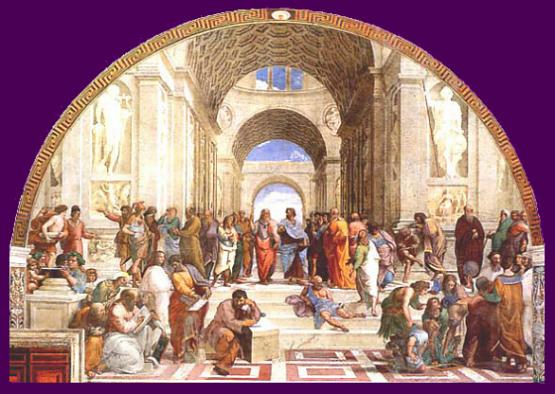

Kate and I just finished a session with our trainer and I feel good. Tired but good. Today is Raphael and Percy Bysse Shelleys birthday (April 6) as well as William Schmidt. Hereís a Raphael painting, The School of Athens:

Rather than Shelleyís poetry here are his thoughts on war: To employ murder as a means of justice is an idea which a man of an enlightened mind will not dwell upon with pleasure. To march forth in rank and file, and all the pomp of streamers and trumpets, for the purpose of shooting at our fellow-men as a mark; to inflict upon them all the variety of wound and anguish; to leave them weltering in their blood; to wander over the field of desolation, and count the number of the dying and the dead,--are employments which in thesis we may maintain to be necessary, but which no good man will contemplate with gratulation and delight. A battle we suppose is won:--thus truth is established, thus the cause of justice is confirmed! It surely requires no common sagacity to discern the connexion between this immense heap of calamities and the assertion of truth or the maintenance of justice. `Kings, and ministers of state, the real authors of the calamity, sit unmolested in their cabinet, while those against whom the fury of the storm is directed are, for the most part, persons who have been trepanned into the service, or who are dragged unwillingly from their peaceful homes into the field of battle. A soldier is a man whose business it is to kill those who never offended him, and who are the innocent martyrs of other men's iniquities. Whatever may become of the abstract question of the justifiableness of war, it seems impossible that the soldier should not be a depraved and unnatural being. To these more serious and momentous considerations it may be proper to add a recollection of the ridiculousness of the military character. It's first constituent is obedience: a soldier is, of all descriptions of men, the most completely a machine; yet his profession inevitably teaches him something of dogmatism, swaggering, and self-consequence: he is like the puppet of a showman, who, at the very time he is made to strut and swell and display the most farcical airs, we perfectly know cannot assume the most insignificant gesture, advance either to the right or the left, but as he is moved by his exhibitor.'--Godwin's Enquirer, Essay v.

One thing Iíve decided to add in here are notes on the people I consider saintsóShelley and Raphael among themóin part because they are important resting points on my pilgrim journey through this life. I go to these saints for refreshment, perspective, guidance, and hope. Our pilgrimage takes us across many lands, some exotic, others mundane, on it we find terror, delight, anguish, and joy. We need inns, like the pilgrims on the road to Santiago, or on the Japanese island of Shikoku with its 88 chapels, or in Glastonbury, like the Pilgrimís there. Our soul needs these rest stops, too, and we find them often in those artists, mystics, architects, musicians who resonant with our journey. I invite you to rest a moment from time to time as I explore some of the rest stops Iíve found along the way. Iíd be delighted to know about yours, too.

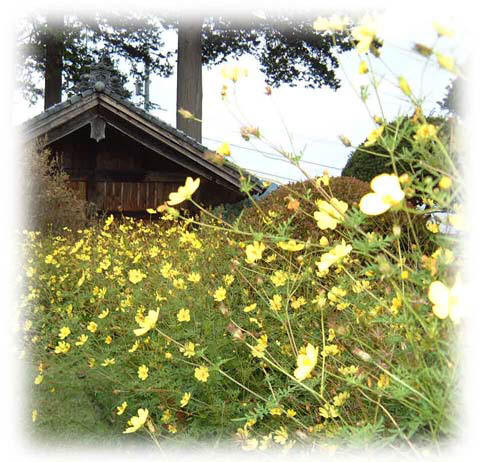

an inn on Shikoku

Clearing up at Semesterís End

I have an end of semester feeling; do you remember? The long narrow tunnel of academics, punctuated by an occasional visit to a bar, an evening with a woman (well, ok, a night), and long hours in the library, classroom opens up to a vista of apparent freedom, winter break, or summer vacation. A long respite from intense intellectual activity and a blessed release from the ability of others to ruin your whole fucking day, hell, last three or four months, with an ill-considered grade. The flowers in the picture are a good analogy to the feeling light, flexible, responding to the sun, opened up, blooming...god, I get goose bumps. No, I have goose bumps. Iím not really completely done. The MIA class has wound down, but I have a tour to design and turn in (if any of you would like a tour of Southeast Asian artóIím your guy.); the Jungian Seminar has one more session, and a good one. It will feature an analyst from Pittsburgh addressing the topic The Black Sun, apparently an alchemical notion of some note. Iíll know more in a month. The first drawing class is done, however, and I have hours behind the pencil, and many more to go before I draw well, but itís been fun, exercised parts of me I didnít even know existed. Still, the pressure to produce weekly is off, and I can concentrate on the complex material for the last seminar session. Feels good. I like my senses. The MIA class teaches me how to see, as does the drawing class. The drawing class teaches me how to feel, to touch, to integrate seeing and touching. This is new for me. This is partly where I get off the Buddhist train as I understand it. I do not feel ensared by my senses, rather, I feel enhanced, enlivened by them. I do not confuse my sensory input with reality, I agree with the Buddha that one way to describe the world our senses present to us is Maya, illusion. I find the senses sweet, incredibly sweet, and vital to my embodied experience. Do they trap me into thinking that this body is all, or even primary? No. But I want to enjoy them while Iím in this state. Iím also on a path toward individuation, that is, realizing my true Self, and being that Self as completely as I can. The Buddhist notion of shunyata, or, no-self, emptiness, empty self seems to me on the very opposite end of a Selfóno-self continuum. Iím too ignorant of both Buddhism and Jung to make a for-sure statement here, but let me try out a thought: In the more family and group oriented cultures of Asia (the nail that stands out gets pounded down and that sort of thing. Face.) the telos of religious or philosophical practice is nirvana, literally, a place of no-self. So, the self becomes completely reabsorbed; the distinctions between and among selves, always tenuous, experience an ultimate deconstruction. In the Western, liberal cultures which focus on individual achievement, individual realization, the telos of religious-psychological practice is the responsible individual, fully known as a unique creation. These two notions feel like axiological distinctions deeply embedded in culture and, in some ways, at least in their extreme, unnuanced states, incompatible. Enough of that for now. Itís rattling around, and I suspect it defines our understanding of pilgrimage. I went out today and removed the hay I used to cover some daffodils, tulips, and crocuses, all cool weather hardy plants. Weíve got some frost still in our future, but these guys can survive. It will be the first of Kateís purple garden to to bloom, save for the fall-blooming crocus from last fall. The earth, the smells of hay and grass, the feel of gloves and a pitchfork, a wheelbarrowís wobbly wayóIím glad its all back. As the semester winds down, I can give myself time in the garden, time to draw... Ahhh.

AM Notes

Havenít written here in the morning, my usual writing time. The good hours. But wanted to finish last nights thought...I cleaned up all the various archival piles I created in the heat of a busy time, did chores, wrote notes, made plans, got reorganized. I love this because it gives me a chance to start fresh, get things in their places, plus I get a quick overview of current work. The crocus, tulips, and daffodils Iíve uncovered push up daily. At this time of year and on into May it seems there is a force beneath, pushing up, helping these plants reach toward the sun. I fell in love with perennial bulbs years ago; they have a pluckiness and a hardiness that make feel glad, especially in the changeable weather of a Minnesota spring. I love to plant them in fall, the tough little bulbs with papery brown skins, feed them, and tuck them to sleep. Then, after their growth spurt has reminded me of resurrection and the creative energy stored even in the bleak times, they bloom. Yellow. Purple. Blue. Red. Waving, cheerful, bright. I walk among them every morning, delighted to see them. Not to mention the anticipation of their coming colors. Des colores. The rainbow coalition of my perennial borders. If there is no other reason for hope, I find it in these sturdy plants, adapted to life in difficult climates with joy and vibrancy. Is there a message here? At least this. On your pilgrim journey stop and notice the daffodils. They created those blooms to attract attention in the first place.

Thought Iíd also start adding your responses as they come, that way this can be a dialogue among us, as well as between you and me:

William Schmidt wrote, in response to #10:

Charlie,

On April 18th I have a presentation to make at Groveland UU again. This time, on a topic of their choosing, ďIs Life Too Hard?Ē I plan to throw in Williamís idea about life as a torture-test, since I think thatís the thrust of the question. As texts for the 18th, I chosen Ingmar Bergmanís The Seventh Seal. (My black and white period.) Groveland member Susan Sternfels added, Winged Migration and The Fast Runner. I watched most of Winged Migration last night and have yet to see The Fast Runner. I own all three, my DVD collection has become an obsession like my library, butówhat quality and the chance to see movies as I read a book, stopping when I want, going back, right away, or later. A true wonder of the technology age as far Iím concerned. Almost as good as high speed internet, but, hey, youíll have to go some to top that in my opinion. Iím sure youíve seen Winged Migration, but if you haven't this is an amazing movie. It recapitulates years of filming from ultra lights, and shows many, many bird species on their migration flights. Aside from the gorgeous cinematography and the sparse narration, I found most striking the visual images, from above, of the birds in flight. I had never seen film, to the best of my knowledge, shot from this angle. The muscular action during flight amazes me; these powerful muscles ripple all across the birdís back, between the two wings, lifting, pushing, pressing, and then, doing it again. The energy expenditure for flight... Whoa! No wonder you never see a fat bird. Watching the movie got me thinking about the topic, Is Life Too Hard? As Susan intended, I know. I got this far with it: from a birdís perspective the answer is, surprisingly, after you see the effort required to migrate, no. Why? Because bird life doesnít have the pleasure and pain of language, at least not language with the kind of self-awareness this question assumes. (At least I donít think so. Anybody know different?) The bird only knows what life requires. Say youíre an Arctic Tern, well, life requires two flights each year from the Arctic to the Antarctic. 12, 500 miles. Any further and youíre on youíre way back. Do the Terns sit around in small Flight Beyond the Sky congregations debating the existential situation in which they find themselves? ďWhy, exactly, do we have to fly half-way around the earth to get more insects? I mean, couldnít there be a better way? Why?Ē No, their bodies listen to the weather and to the stars, and, when the seasons and the stars line up, off they go, no matter how far, no matter how difficult. And many, many fall by the side on the trip. The annual pilgrimage from food-rich geography to also food-rich geography thousands of miles away costs many birds their lives. The pilgrimage thins the flock. No, for us, the question Is life too hard rests on understanding each word, each concept inherent in the question. Long ago, in a far away land, a wise old man taught me the rudiments of linguistic analysis. And I remember them as ideas lost, for the most part, in the mists of time. This much I recall. Is life too hard? What do we agree these words mean? All four, plus the question mark. All of philosophy teaches us to answer a question, we must first understand the question itself. Is is the substantive verb in English. Wrapped up within it are some of the deepest and most enigmatic questions humans can ask. What does it mean to be? What is, is? Is assumes we have an answer to a most perplexing question, the nature of the world we perceive through our senses. (No, weíre not going back to the Buddha here, though, I must note, we could if we felt like it.) In this case I think is carries an even more freighted meaning, i.e. to have isness, in this case, to be alive and therefore part of this worldóin other words, it describes the context of the question, life is a question of being and the nature of being alive is the question. Then, life. The word itself. Life. Well, there is an entire, millennia old debate between two ancient schools of thought: the mechanists and the vitalists. Boils down to this, are living things merely the sum of their parts? If so, though fascinating, living things are no more than complex, difficult to understand machines. Certainly the whole DNA, proteomics, robotics, prosthetics, and certain schools of the brain/mind debate lead us toward a mechanistic perspective. Or, the vitalistís question, are living things more than the sum of their parts? Is there some spark, some elan vital, a breath of God that makes life essentially different from the mere sum of the parts, a very interesting machine. Then, in one sense, the heart of the question, the word too. Each of us would, I assume, agree that life, at its best, is hard? It may not be unrelenting, may not be dismal, may not be apparently tragic all the time, but, life is hard. Note, we havenít discussed the word hard yet. But still. Letís assume for the moment we agree on a common sense meaning of hard. Letís say, difficult. Well, life is difficult. Wonderful, yes, but difficult, too, surely? It is this the intensification, the intensifier of the question, too, that makes this question stop us for moment, gives us pause. We wonder, huh, maybe life isnít just hard, maybe it is too hard. The implication of saying yes could be quite drastic, couldnít it? If we all agreed, yes, life is too hard, wouldnít we be giving tacit assent to suicide? If life is too hard, well, then...(more later)

Yesterday was the birthday of William Wordsworth, born April 7, 1770. His work and that of Samuel Taylor Coleridge began the Romantic movement. I find myself part of a neo-Romantic, neo-Pagan sensibility, perhaps not in a formal way, but certainly in my overall attitude toward life.

William had met the

poet

Samuel Taylor Coleridge,

an enthusiastic admirer of his early poetic efforts, and in 1797 he

and Dorothy moved to Alfoxden, Somersetshire, near Coleridge's home in

Nether Stowey. The move marked the beginning of a close and enduring

friendship between the poets. In the ensuing period they collaborated on a

book of poems entitled Lyrical Ballads, first published in 1798.

http://www.island-of-freedom.com/WORDSWOR.HTM (italics above mine)

You can see from the italicized sentence how I relate to these folks, and why Buddhism and I have different paths. The pilgrimage of one devoted to direct experience of the senses separates him from those who attempt to disassociate themselves from the senses. I love much of Buddhist thought and practice, yet at the level of axiology (first principles, assumptions, starting points) I find profound conflict.

THE WORLD IS TOO MUCH WITH US

Iíve sent this poem out two times on the Great Wheel e-mail, but it says so much of my pilgrimage, where Iíve been and where Iím headed. Wordsworth is, for me, a true saint.

The Miracle, Hellboy, The Passion of Christ, Dawn of the Dead

In my theological opinion this would make a great marquee on some drive-in theatre later in the summer. Saw Hellboy today, Good Friday, along with ten other pagans. A surprisingly good movie, tight, interesting, CG used to good effect. I was not familiar with the comic book, but Iím all in favor of comics becoming movies. I liked American Splendor, Spiderman, X-Men especially. Not such a big fan of the Superman and Batman movies. Too broad, not enough angst for me. Still, this is Easter weekend, the high holy days of the Christian liturgical year, and I vibrate in tune with them. Literally. Found myself humming Hopping Down the Bunny Trail, In my Easter bonnet, Morning has broken... And meditating on the significance of death and resurrection. It is possible to view the Christian liturgical year as a pilgrimage, in imitation, perhaps, of the Great Wheel. From this perspective the human spiritual path starts long, long ago in the Garden of Eden with the creation of Adam and Eve. As limited creatures, created with the limits of sense perception and the reach of the human mind and heart, our forebears made mistakes, as we, their children, still do, and for the same reasons: our limited ability to grasp our situation and the divine intent for us in it. The pilgrim journey of the human spirit began with the ejection of Adam and Eve from the east gate of Eden, suffered a dramatic setback with the Flood, then, a chastened God set the rainbow in the sky and agreed to let humanity develop as it would. It was not long after that Abram got the call, in Ur of the Chaldees, to go forth to Canaan, the promised land, where his descendants would be as the stars in the heavens. Thus, the story of the chosen people unfolded over the millennia until, in act of desperate and literally self-sacrificing love, God impregnated a young Jewish woman, unmarried. Mary. At the birth of Jesus, son of Joseph and Mary and Yahweh, the Christian liturgical year begins. (Advent, for the longest part of liturgical history, did not focus on the advent of Jesus, but on the advent of the second coming, and so had a liturgical tone and significance much more like current Lent.) Jesus' birth brings in the question of divinity in human form, incarnation, and the complex issues decided for most Christians in the Chalcedonian formula, Jesus is both man and God. The liturgical pilgrimage begun in the birth narrative moves through the visitation of the Wisemen at Epiphany, then the season of Lent, preparatory to Holy Week, which includes Good Friday and Easter Sunday. After Easter the ascension, then Pentecost, when the holy spirit completed the Trinity and transmitted the power of Godís spirit to the followers of Jesus. After Pentecost, the church moves into the wonderful liturgical season of Ordinary Time. Thus the Christian year is a pilgrimage of the spirit from the majesty of God coming to earth in human form, living an earthly life, then suffering a painful death, and, through Godís own intervention, defeating death and spreading the good news of Godís victory over death throughout the world, in holy and in ordinary time. It is in this rhythm that Advent, in the old sense, ended the liturgical year with the theologically completed journey, through suffering, death, resurrection, history, and ending, finally, after the four horsemen have ridden and the seven seals have opened. It is a pilgrimage I respect and one that still has power to move me, yet it is, also, no longer my sole, nor my soul pilgrimage. I have taken a different path, one away from Golgotha, a path that leads more through Greece, Rome, and the fields of Europe.

Which two books to take on pilgrimage? Well, geez. After some thought, though, Iíve hit on an answer, but it must disallow weight as a factor. No. No. Not the OED, although it would be handy. And, no, not Webster's III. No, Iíve decided to take the New Revised Version of the Bible and the New Oxford Book of English Verse. The first, because, even though demythologized for the most part, it is still the seminal book for my religious journey, a pilgrimage now of long standing. Also, itís full of good stories, poetry, history, cultural critique, myths and legends. It is a good read. The New Oxford Book of English Verse has similar virtues. Poetry has played a major role in my faith journey, and I need the familiar words, as well as the unfamiliar, just like in the Bible. The familiar words for comfort and the unfamiliar for entertainment and further stimulation. The New Oxford Book of English Verse may, by the 19th, have a replacement. Iím taken, very much, with American poetry and if I can find a similar compilation of American poetryówith large doses of Whitman, Stevens, Edna St. Millay, Bly, White, Oliver, Hall, Collins, Berry, Dos Passos, Ferlinghetti, Ginsburg, Lowell I may choose it. I realize these are conservative choices. So, there you are. I am a foundationalist in this regard, and believe a thorough knowledge of the classics still produces an educated and enlightened person. A humanist, too. So, letís see, foundationalist, liberal religionist, humanist, neo-Romantic, neo-Pagan, neo-Jungian, political liberal, classical aesthete in literature and the visual artsóand, of course, at the same time, their dialectical opposites, though these are the poles at which I start my journeys of opposition. I learned a couple of months ago about transcendent functions. Did I mention that here? No? Itís a Jungian (maybe others, too) method of transcending dialectical tension, also called the union of opposites. In a true union of opposites, both sides of a dialectic remain, held in their distinctiveness, yet they become part of a third, transcendent union, psycheís way of creating a functionality inclusive of both poles. Charlie Buchman Ellis Top < Previous Next > |